ROMANCE

Fourth River

Cay Bahnmiller, Jono Coles, Sophia DiRenna, Finn Dugan, Justin Emmanuel Dumas, Armanis Fuentes, Sophie Friedman-Pappas, Alice Gong Xiaowen, Max Guy, Katherine Hubbard, Kahlil Robert Irving, Robert Lepper, Erin Jane Nelson, Ido Radon, Jerome Sicard, Harrison Kinnane Smith

May 31–Aug 17, 2025

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Sophie Friedman Pappas

Kiln Building 4, 2025

Self-glazed kiln and mixed media

7 1/2 x 13 1/4 x 11 in.

Sophie Friedman Pappas

Kiln Building 4, 2025

Self-glazed kiln and mixed media

7 1/2 x 13 1/4 x 11 in.

Sophie Friedman Pappas

Kiln Building 4, 2025

Self-glazed kiln and mixed media

7 1/2 x 13 1/4 x 11 in.

Sophie Friedman Pappas

Kiln Building 4, 2025

Self-glazed kiln and mixed media

7 1/2 x 13 1/4 x 11 in.

Alice Gong

Clasp, 2025

Soapstone, stainless steel exhaust V band clamp

3 x 3 ½ x 1 in.

Alice Gong Xiaowen

Clasp, 2025

Soapstone, stainless steel exhaust V band clamp

3 x 3 ½ x 1 in.

Alice Gong Xiaowen

Clasp, 2025

Soapstone, stainless steel exhaust V band clamp

3 x 3 ½ x 1 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

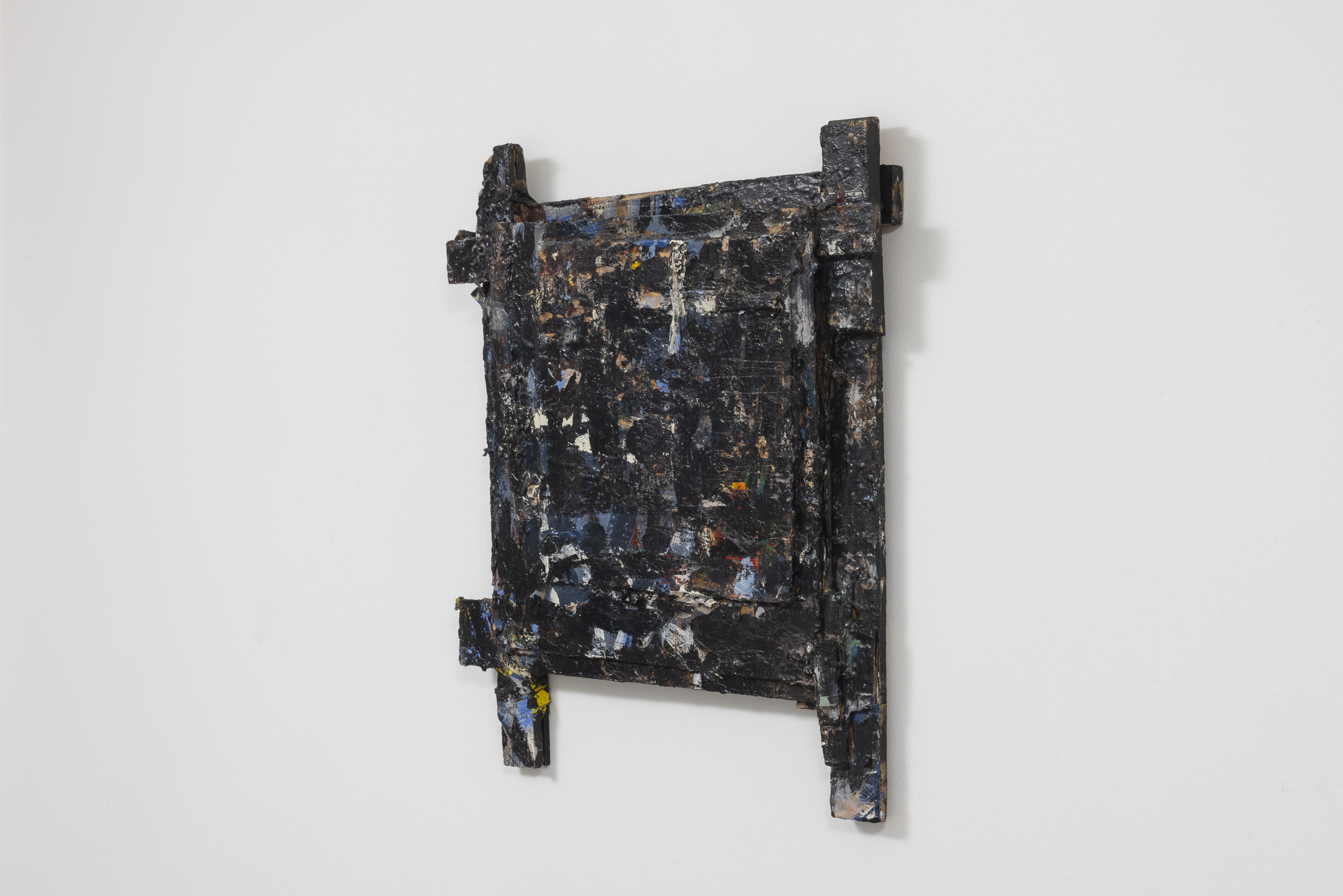

Cay Bahnmiller

Untitled, 2003-24

Mixed media

20 x 20 in.

Cay Bahnmiller

Untitled, 2003-24

Mixed media

20 x 20 in.

Cay Bahnmiller

Untitled, 2003-24

Mixed media

20 x 20 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Kahlil Robert Irving

Stella: bye BLUE:STARlight [{bells ring for freedom], 2022

Glazed and unglazed ceramic, personally constructed decals, gold, blue, silver,

opalescent luster, wood

55 x 55 x 4 in.

Kahlil Robert Irving

Stella: bye BLUE:STARlight [{bells ring for freedom], 2022

Glazed and unglazed ceramic, personally constructed decals, gold, blue, silver,

opalescent luster, wood

55 x 55 x 4 in.

Kahlil Robert Irving

Stella: bye BLUE:STARlight [{bells ring for freedom], 2022

Glazed and unglazed ceramic, personally constructed decals, gold, blue, silver,

opalescent luster, wood

55 x 55 x 4 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Justin Emmanuel Dumas

Still Water Runoff, 2025

Hardware, copper mesh, aluminum sheet, salvaged silk screen, thread, fishing line, latex milk, ammonia

23 x 19 in.

Justin Emmanuel Dumas

Still Water Runoff, 2025

Hardware, copper mesh, aluminum sheet, salvaged silk screen, thread, fishing line, latex milk, ammonia

23 x 19 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Alice Gong Xiaowen

The lowly hallowed, 2023

Cast iron

28 x 14 x 8 in.

Alice Gong Xiaowen

The lowly hallowed, 2023

Cast iron

28 x 14 x 8 in.

Armanis Fuentes

Untitled, 2025

Intonaco (fresco) on brick shard

4 ½ x 2 x 2 in.

Armanis Fuentes

Untitled, 2025

Intonaco (fresco) on brick shard

4 ½ x 2 x 2 in.

Finn Dugan

star, 2024

Concrete and plaster

5 x 5 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Armanis Fuentes

Untitled, 2025

Intonaco (fresco) on brick shard

4 ½ x 2 x 2 in.

Armanis Fuentes

Untitled, 2025

Intonaco (fresco) on brick shard

4 ½ x 2 x 2 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

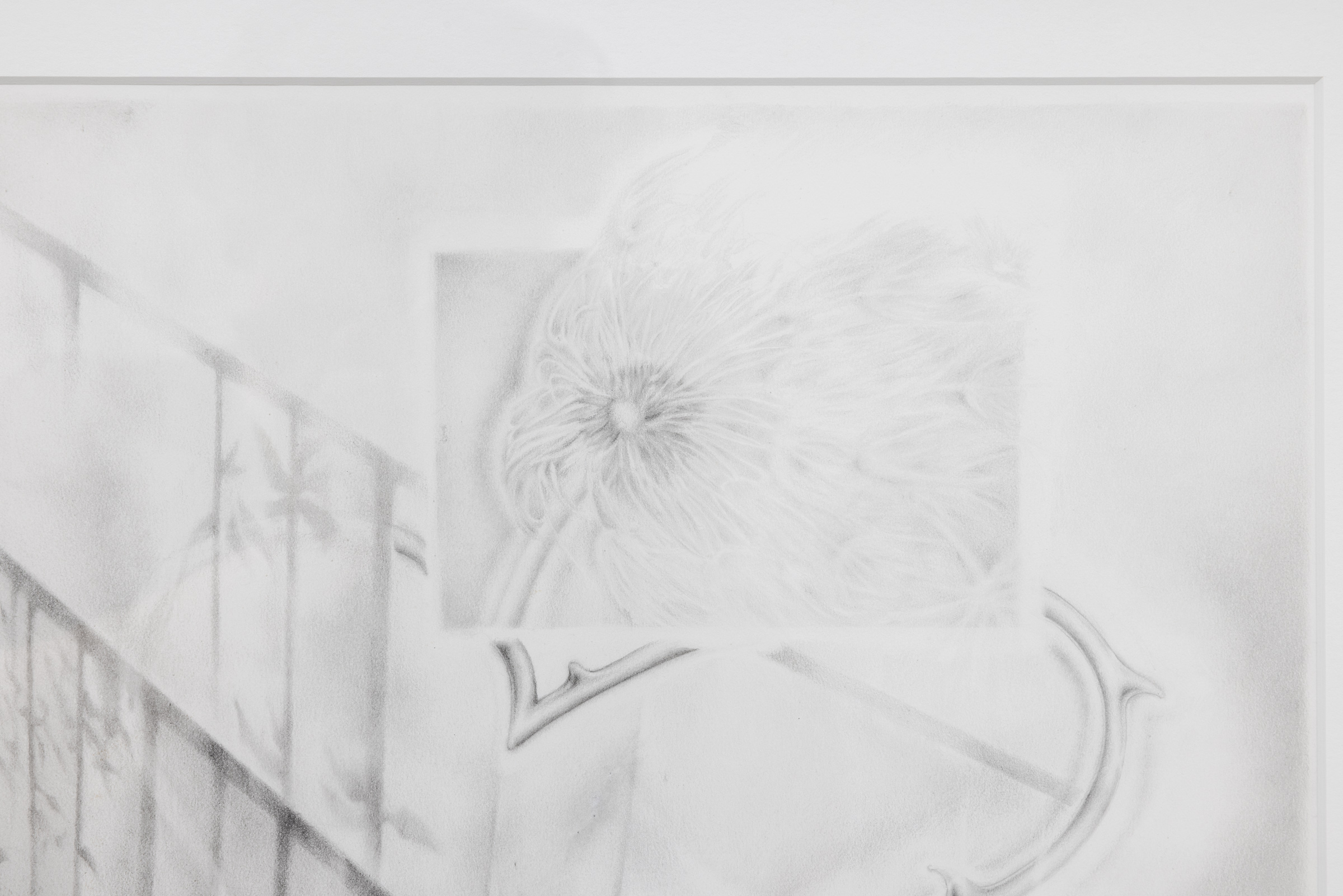

Sophia DiRenna

Walking, Running, Sitting, 2024

Graphite on paper

19 x 22 in. (framed)

Sophia DiRenna

Walking, Running, Sitting, 2024

Graphite on paper

19 x 22 in. (framed)

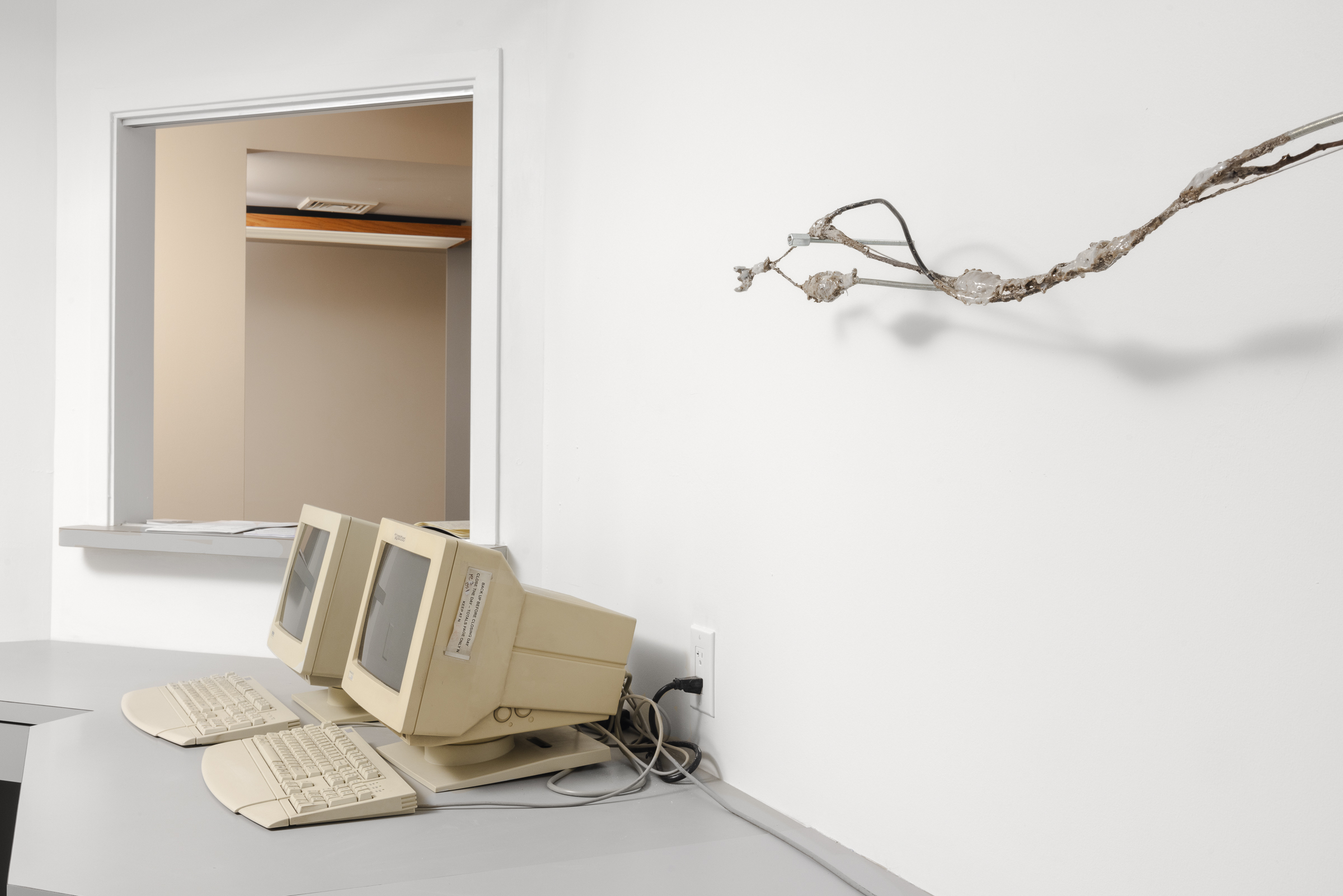

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Finn Dugan

may, 2025

Branch, aluminum, wire, clay, ash, marble dust, resin

54 x 4 x 3 ½ in.

Finn Dugan

may, 2025

Branch, aluminum, wire, clay, ash, marble dust, resin

54 x 4 x 3 ½ in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Erin Jane Nelson

Frenier, 2018

Resin, pine cone, glass, and pigment print on glazed earthenware

10 ¾ x 11 3/4 x 3 in.

Erin Jane Nelson

Frenier, 2018

Resin, pine cone, glass, and pigment print on glazed earthenware

10 ¾ x 11 3/4 x 3 in.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Robert Lepper

Untitled, 1959

Aluminum, masonite, brass crews and nuts

31 1/4 x 32 1/4 x 18 in.

The Marty O’Brien Collection of American Art

Jerome Sicard

Lancaster (2), 2025

Ammunition box, casters, kantha quilt, key chain, pewter milagros, phragmites, string, twine.

45 x 12 x 17 in.

Jerome Sicard

Lancaster (2), 2025

Ammunition box, casters, kantha quilt, key chain, pewter milagros, phragmites, string, twine.

45 x 12 x 17 in.

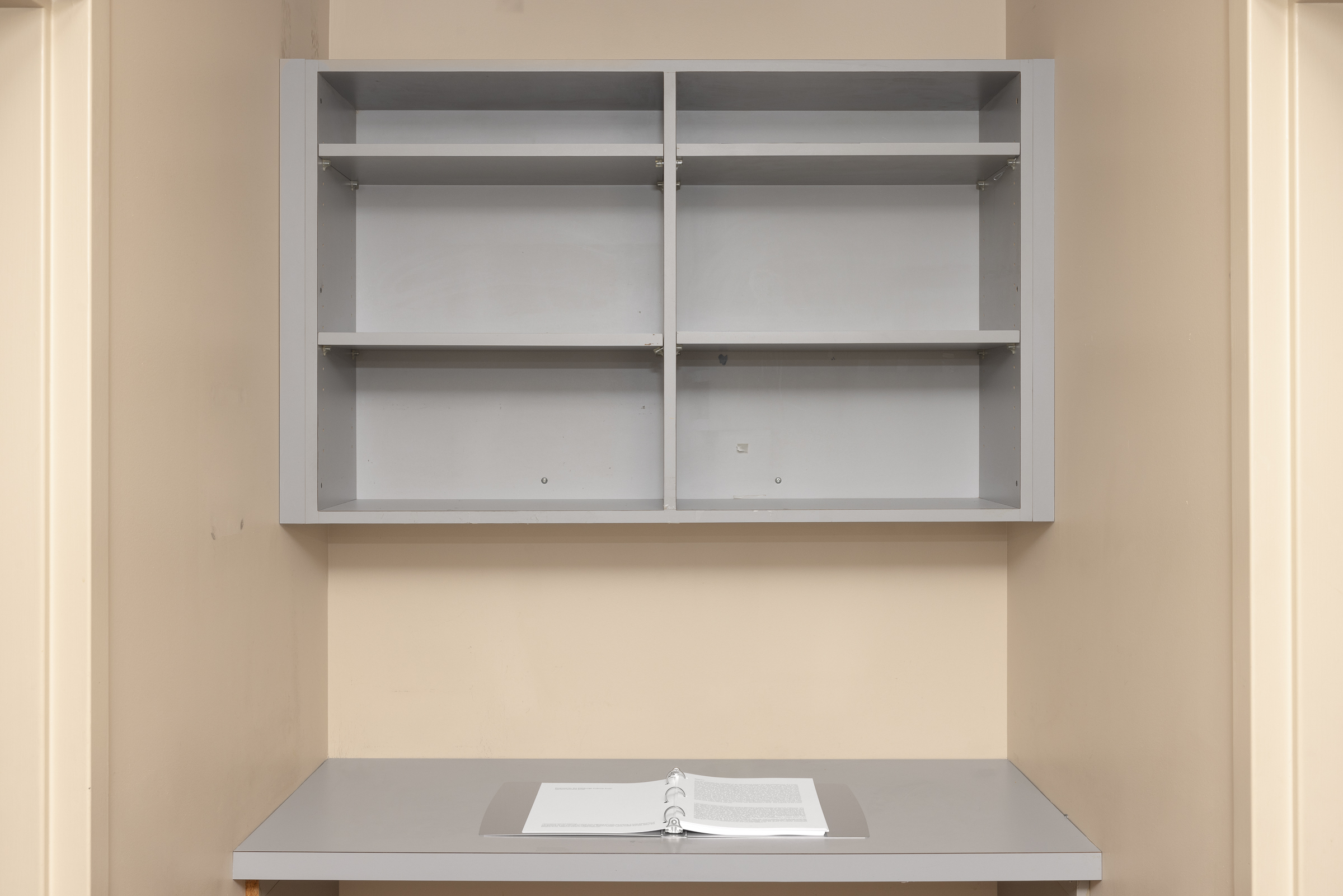

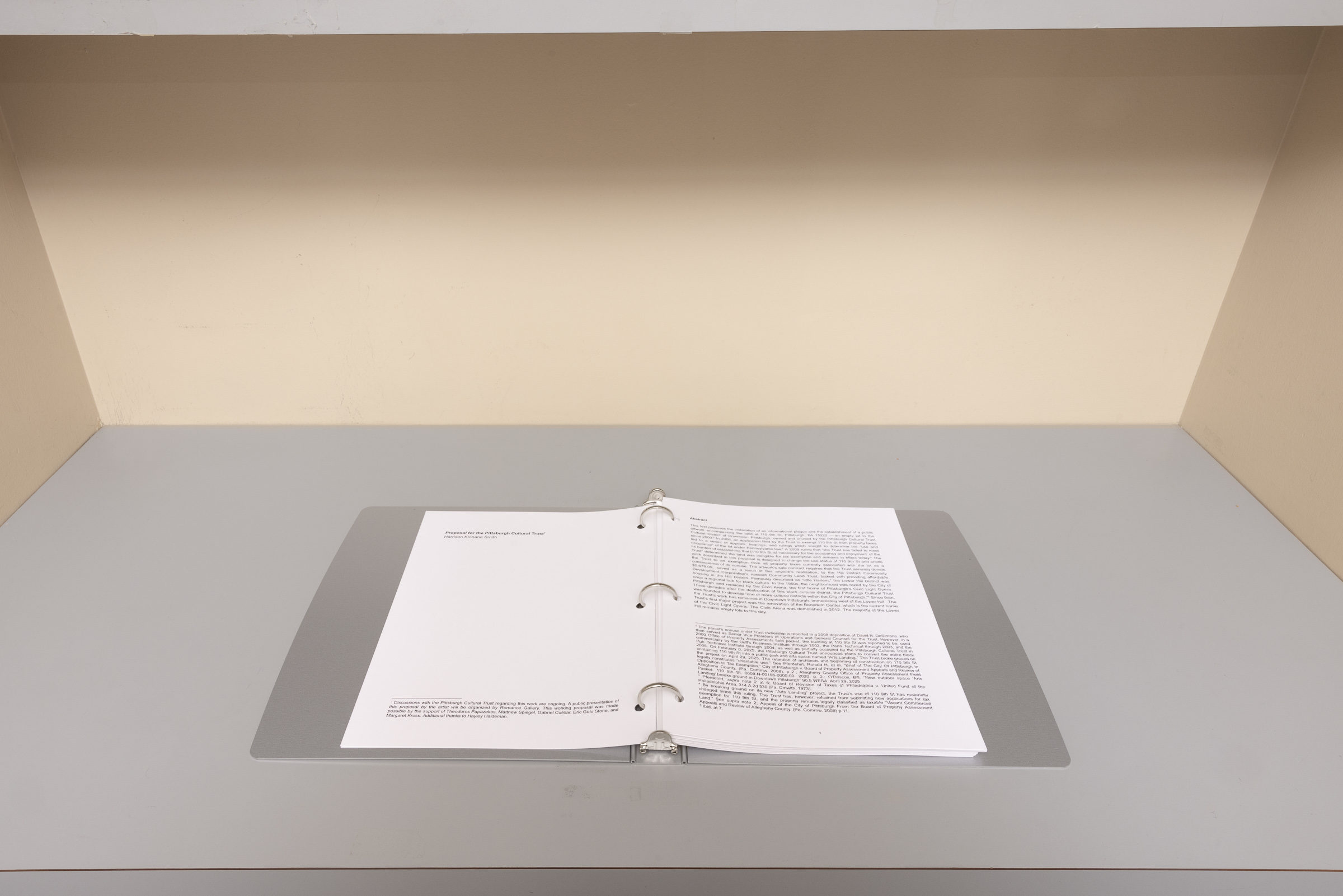

Harrison Kinnane Smith

Proposal for the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, 2025

Inkjet print on paper, binder

13 x 10 x 2 in.

Harrison Kinnane Smith

Proposal for the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, 2025

Inkjet print on paper, binder

13 x 10 x 2 in.

Ido Radon

Sympathy for the living, 2025

MDF plexiglass, steel, iron slag

19 x 17 x 12 in.

Ido Radon

Sympathy for the living, 2025

MDF plexiglass, steel, iron slag

19 x 17 x 12 in.

Ido Radon

Sympathy for the living, 2025

MDF plexiglass, steel, iron slag

19 x 17 x 12 in.

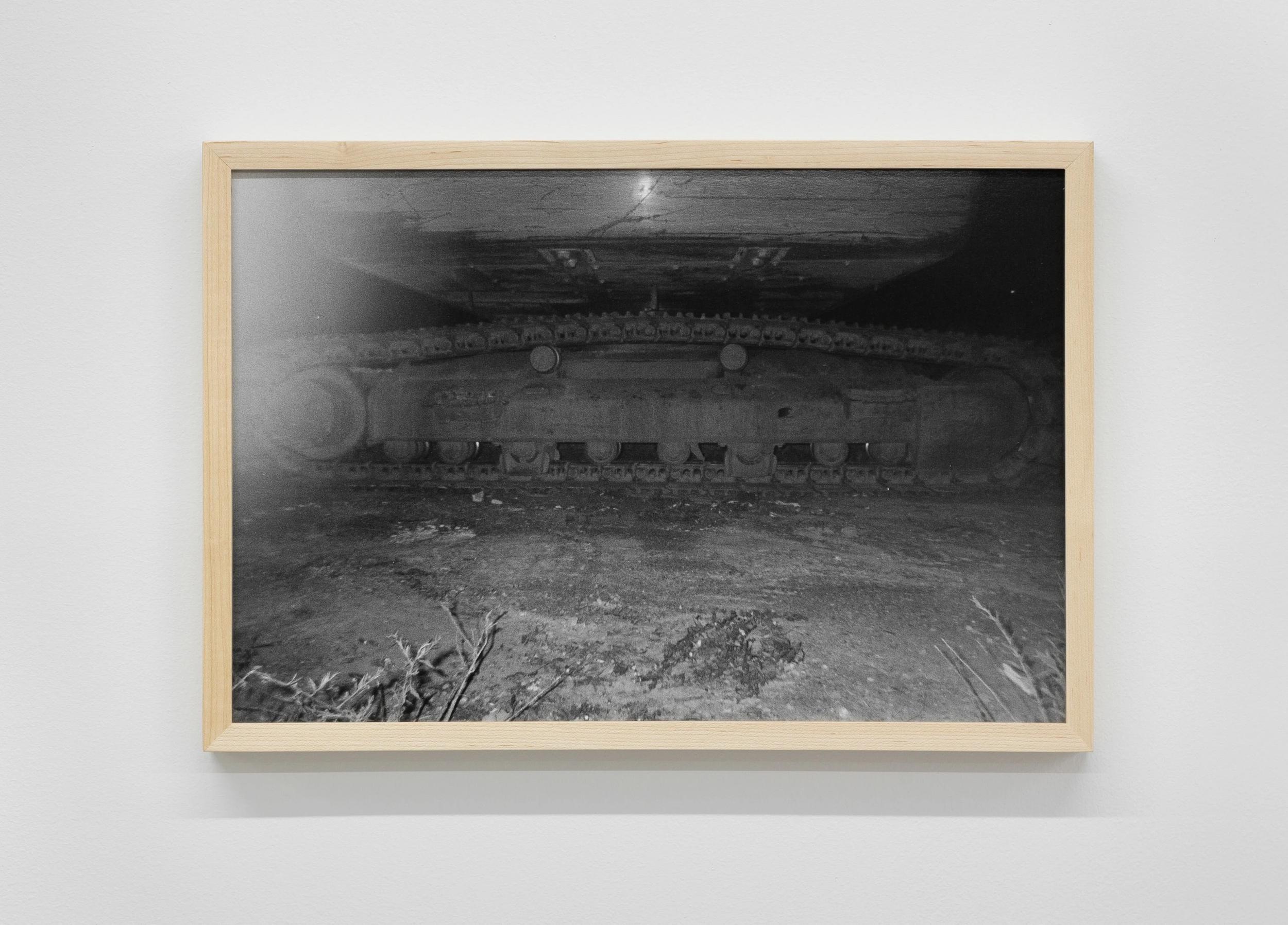

Katherine Hubbard

untitled (tread), 2019

Silver gelatin print

Edition of 2 plus 2 AP

11 x 17 in. (framed)

Katherine Hubbard

untitled (tread), 2019

Silver gelatin print

Edition of 2 plus 2 AP

11 x 17 in. (framed)

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Installation view, Fourth River, 2025.

Jono Coles

Office2, 2025

Inkjet print on matboard

14 x 11 in.

Max Guy

No Reason (2020 Cut)

Single-channel video and auxiliary AM and FM transmission

Max Guy

No Reason (still), 2020 Cut

Courtesy of the artist

Max Guy

No Reason (2020 Cut)

Single-channel video and auxiliary AM and FM transmission

Max Guy

No Reason (still), 2020 Cut

Courtesy of the artist

Photos: Chris Uhren.

A body of water is buried beneath Pittsburgh; local lore refers to it as the “Fourth River.” A river below the city and its sharp downtown skyline is a surreal image, suggesting the possibility of an underworld free from urban development and capital. Prior to the formation of city’s three defining rivers, this region known as Pittsburgh marked the edge of a shallow ocean running across the Midwest and today constitutes the easternmost edge of a large swath of the US known as the Mississippi River Basin. As a result of these easy trade routes, the city fell prey to the industrialists, starchitects, and urban planners (Olmsted then Moses then Wright) of the early 20th century.

This exhibition brings together works that consider how cultural myth shapes cities and, in turn, the emotional experience of not just the individuals who live there, but the psychological energy contained within a place itself. The show uses the Fourth River and its connection to other mythological waterways—namely, the Ohio to the Mississippi River—as metaphor for the emotional impact of American ideology and cultural myth on the built world. The specific works discussed here share visual affinities: a resemblance to memorials or memento mori; abstracted expanses of material that highlight a surface’s physicality: where ideology meets emotion meets materiality in an accumulation or conglomeration of matter and narrative; and, finally, borrowing from historical Conceptualism, through surreptitious documentation of polluted modernism.

Pittsburgh’s urban environment served in the mid-20th century as a blueprint for cities moving toward the west into the region of the United States connected by the Mississippi River. “[T]he ambitious program of revitalization that transformed Pittsburgh quickly became a model for other US cities,” Ed Simon crucially explains in An Alternative History of Pittsburgh. He also noted that “even in those early days, people seemed to have a vision of what America might become and realized the strategic position Pittsburgh occupied in regard to the development in the West.” Further, “the ugliest depths of the American character would become manifest in Pittsburgh as well.”

Not unlike American exceptionalism informing the modern city for which Pittsburgh was a microcosm, the surreal image of ever-plentifal free flowing Fourth River is a mirage. It is, in fact, an aquifer formed by the Wisconsin Glacial Flow, through which a conglomeration of underground cracked stone and sediment have given form to a subterranean landform increasingly blocked by concrete and drained for drinking water and air conditioning and, as it’s told, the towering Point Park Fountain at the headwaters of the Ohio. The fountain, often linked to Wright’s unbuilt 1947 Civic Center proposal, was completed decades later as part of mid-century redevelopment efforts. “Yosemite meets Vegas,” as artist Ido Radon describes it, with its one-acre infinity pool and LED lights installed in 2013 to mark a new-age modernity.

The simultaneity of the city’s corroded past alongside its grabs for futurity expose the failure of not just the post-industrial period for which it is known, but of “The Most Livable City” as conceived today with the hegemonic smoothing over in overlays of vacant condo developments and rapid tech expansion. With the courtship of Uber, the dominance of Google and Duolingo and AI robotics, the monopoly of the UPMC health conglomerate, there is a palpable kind of mourning here: not of the steel industry’s failure, but of a deadening present that only by surfacing its unseen truths can it truly move forward. Not as a problem to solve with a “solution” but a being present in its stored psychological energy and resulting material realities.

The landmark in many respects feels like a gravestone for the Fourth River—a repository of grief and psychological toxicity that modernism’s model of the city holds. Aimed at expanding the city beyond the machine age, Pittsburgh’s two Renaissances sought to manifest Enlightenment ideals favoring the disembodied mind and an intentional forgetting. For Robert Smithson, the modern city “forgets that the earth exists.” So “Most Livable City” for who and for what kind of life? The collective imaginary often thinks of Pittsburgh as the farthest thing from romantic. But it is, in the sense that it is a city built on the faulty ground of idealization and limerence. Love, in contrast, is rooted in facing grief and conflict, facing material realties that impact our emotional wellbeing, which the city at large often hesitates to acknowledge. Perhaps, this exhibition considers, a new affective understanding of place can find new cracks and creeks underground. As David Harvey writes in The Right to the City:

The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of daily life we desire, what kinds of technologies we deem appropriate,what aesthetic values we hold. The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individual access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire. […]

--

Cay Bahnmiller (b. 1955, Wayne, MI; d. 2007, Detroit, MI) was an artist primarily based in Detroit. During her lifetime, her work was shown at Feigenson Gallery and Susanne Hilberry Gallery in Detroit and was collected by Gilbert and Lila Silverman. Her work is in the collections of the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the University of Michigan Museum of Art. Since her passing her work has been shown at What Pipeline in Detroit. She graduated from the University of Michigan in 1976.

Jono Coles (b. 1997, Pittsburgh) works between art practice and architectural practice to interrogate the financialization of built space. Based between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh, he holds a Master of Architecture from UC Berkeley.

Sophia DiRenna (b.1998, Pittsburgh, PA) is a graphite artist based in in Pittsburgh who received her BFA from Chatham University in Printmaking and has exhibited her work at various galleries in the area, including Bottom Feeder & Inter Pgh. In 2023 she attended the Tongue River Artist Residency in Dayton, Wyoming.

Finn Dugan (b. 2000, Pittsburgh, PA) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Pittsbrgh who’s practice fuses digital technology, animation, found objects, biological, and industrial materials. Dugan’s work exhibited at the Tomayko Foundation, Brew House Arts, Plexus Projects, Mid-America College Artists Association (MACAA) , and Sculpture X, among others. He was awarded juror’s award from MACAA, Sculpture X, and received residencies from Brew House Arts (Pittsburgh, PA) and Popps Packing (Detroit, MI). Dugan graduated from Allegheny College in 2022 studying Art and Physics and is currently based in Pittsburgh, PA.

Justin Emmanuel Dumas (b. 1994, Pittsburgh, PA) is an artist based in Pittsburgh, PA. He graduated from Yale University as part of the Painting and Printmaking MFA Class of 2024. His work has been shown at the Carnegie Museum of Art and multiple galleries across the US and internationally).

Armanis Fuentes (b. 1997, Bayamon, PR) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Pittsburgh, PA who received a BA in Art History and Studio from Williams College and an AA in Liberal Arts from Holyoke Community College. Fuentes is a member of the artist collective hotbed, participated in Brew House’s 2023 – 2024 Distillery Program and has recently been resident at Bunker Projects. Drawing from art history, Caribbean cosmologies, and their own family history of domestic labor, Fuentes’s work injects fantasy into the mundane, underscoring a fragile truce between The Worker and The Home, between the body and the industry of homemaking.

Sophie Friedman-Pappas (b. 1995, New York, NY) lives and works between Los Angeles and New York. She received her MFA from UCLA in 2024, and her BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art in 2017. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions of Friedman-Pappas' works include List Projects 28: Sophie Friedman-Pappas and TJ Shin, MIT List Center, Cambridge, USA (2023-2024); Lacker (with Maren Karlson), in lieu, Los Angeles, USA (2023); Hannah Black and Sophie Friedman-Pappas, Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York, USA (2022); and Transfer Station (organized by Octagon), Alyssa Davis Gallery, New York, USA (2021). Selected group exhibitions of her works include Scupper, Francois Ghebaly, Los Angeles, USA (2024); Hot, Art Lot, Brooklyn, USA (2024); Unlife: Part II, Soft Opening, London, UK (2024); Unlife: Part I, Soft Opening at Paul Soto, Los Angeles, USA (2023); Inaugural Show, Bodenrader, Chicago, USA (2023); Scouring, Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York, USA (2022); and The Devil Knows, Simone Subal, New York, USA (2022).

Alice Gong Xiaowen (b. 1994, in Beijing, China) lives and works in New Haven. She received her BFA from School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2016 and a MFA in Sculpture from the Yale School of Art in 2025. Her recent solo and two-person exhibitions include: Sustain, Gallery Vacancy, Shanghai, 2025; Asymptote, circling, CHAMBER lower cavity, Holyoke, 2024; Malar, House of Seiko, San Francisco, 2023. Group exhibitions include: Fourth River, Romance, Pittsburgh, 2025; Can Thought Go On Without a Body?, Stilllife, New York, 2024; Adaptation, Franz Kaka, Toronto, 2024; In Summer's Teeth, Silke Lindner, New York, 2023; Bury the Bridge, DUPLEX, New York, 2022. She is the recipient of the Explore and Create Grant from Canadian Council for the Arts, 2022; the UrbanGlass Winter Scholarship Award, 2019; and the John W. Kurtich Foundation Travel Fellowship, 2015.

Max Guy (b. 1989 McAllen, Texas) lives in Chicago, Illinois. Guy works with paper, video, performance, assemblage, and installation and uses fast, ergonomic ways to make poetry of the world, filtering it through personal effects. Guy received a BFA in 2011 from Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and an MFA in 2016 from Northwestern University. He has exhibited nationally and internationally, most significantly with solo exhibitions at The Renaissance Society (Chicago) and in The Drawing Room at The Arts Club of Chicago, as well as Good Weather (Chicago), part of the group exhibition We Buy Gold 7 at Jack Shainman (New York) and Nicola Vassell (New York) in 2023. He has also presented work in exhibitions at AND NOW (Dallas), Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago, Romance (Pittsburgh), Laurel Gitlen (New York), Kai Matsumiya (New York), Each Modern (Taipei), Gallery 400 (Chicago), Krannert Museum of Art (Urbana-Champaign), Produce Model (Chicago), Apparatus Projects (Chicago), Prairie (Chicago), Malmö Museum of Art (Malmö, Sweden), BAR4000 (Chicago), CAVE (Detroit), Chicago Cultural Center, and Galeria Federico Vavassori (Milan, Italy), among others.

Katherine Hubbard (b. 1981) is an interdisciplinary artist whose work engages the intersections of photography, performance, and text. Considering analog photography as a mimesis of the body, Hubbard asks how its procedures might be called upon to investigate social politics, history, and narrative. Solo exhibitions include The great room, Company Gallery, New York (2023); Avoid glancing blows, Company Gallery, New York (2020); Katherine Hubbard, Higher Pictures, New York (2018); stages, Baxter St. Camera Club of New York, New York (2017); and Bring your own lights, The Kitchen, New York (2016). Her work has been exhibited in group exhibitions including Time Management Techniques, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Ecstatic Land, Marfa Ballroom, Texas; A Collection of Slow Events, The Luminary, St. Louis, Missouri; The Artist’s Museum, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; and Greater New York, MoMA PS1. Hubbard’s performances have been presented at the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas; Konstfack, Stockholm, Sweden; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Hubbard received her MFA in 2010 from the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College and is currently an Associate Professor of Art and MFA Graduate Director at Carnegie Mellon University School of Art.

Kahlil Robert Irving (b. 1992, San Diego, CA) spent most of his youth in St. Louis, Missouri where he currently lives and works. He attended the Kansas City Art Institute, where he received his BFA, and earned his MFA from the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Art at Washington University in St. Louis. Irving’s work has been featured in numerous group exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, the New Museum, and the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. In February of 2024, Irving opened concurrent exhibitions at the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art (AnticKS & MOdels + My theater to your eyes) and Archeology of the Present at the Kemper Art Museum in Saint Louis.

Robert Lepper (1906-1991) was an American artist and art professor at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, who developed the country's first industrial design degree program.[1] Lepper's work in industrial design, his fascination with the impact of technology on society and its potential role for artmaking formed the background for his class "Individual and Social Analysis", a two semester class focusing on community and personal memory as factors in artistic expression, which with his theoretical dialogues with his most promising students outside the classroom fostered the intellectual environment from which such diverse artists as Andy Warhol, Philip Pearlstein, Mel Bochner, and Jonathan Borofsky would later build their art practices

Erin Jane Nelson (b. 1989, Neenah, WI) is an artist based in Santa Fe, NM. Nelson received her BFA from The Cooper Union in 2011. She has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, Atlanta; Chapter NY, New York; DOCUMENT, Chicago; and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Atlanta; among others. Her work was included in the 2021 New Museum Triennial and has been included in group exhibitions at the Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Moss Art Center, Virginia Tech; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Aspen Art Museum, Aspen; the Fries Museum in Leeuwarden, NLD; La Galerie, centre d’art contemporain, Noisy-le-Sec; Deli Gallery, New York; Van Doren Waxter, New York; Capital Gallery, San Francisco; and the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich. Nelson is a recipient of the 2023 Guggenheim Fellowship.

Ido Radon is an artist based between Portland, OR and Vancouver. Her practice grapples with abstractions that structure the social real even as they remain impossible to figure. Forms emerge from historical research to include the social, the engineered or infrastructural or technological as these concern human capacities for and impulses for new forms of life under the conditions of modernity. Obviously this means confronting failure and incompletion. This inquiry is theoretically grounded and necessarily dialectical. Radon has made solo exhibitions at Artspeak (Vancouver, B.C), Air de Paris (Paris), Ditch Projects (Springfield, OR), Et al. (San Francisco), Jupiter Woods (London), Pied-à-terre (San Francisco), Romance (Pittsburgh), and Veronica (Seattle) and shown work at Canton Sardine (Vancouver, BC), Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, RONGWRONG, the Belkin Art Gallery, and the Henry Art Gallery. An autodidact, she holds an MFA from the University of British Columbia. With family and friends, she makes SOCIETY.

Jerome Sicard (b. 1997, Pittsburgh, PA) draws on the unique semiotic landscape of his Western Pennsylvanian home to reveal and critique the mythologies underlying American identity. Sicard’s narrative and research-based projects blur the lines between truth and fiction, sincerity and satire, parody and pastiche, while remaining grounded in the cultural heritage of Appalachian America.

Harrison Kinnane Smith (b. 1997, Pittsburgh, PA) is an artist based in Los Angeles. His collaborative work and site-specific interventions critique public institutions and financial systems. His work has been published by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and included in exhibitions at François Ghebaly, LA; SculptureCenter, NYC; and the Mattress Factory Museum in Pittsburgh.