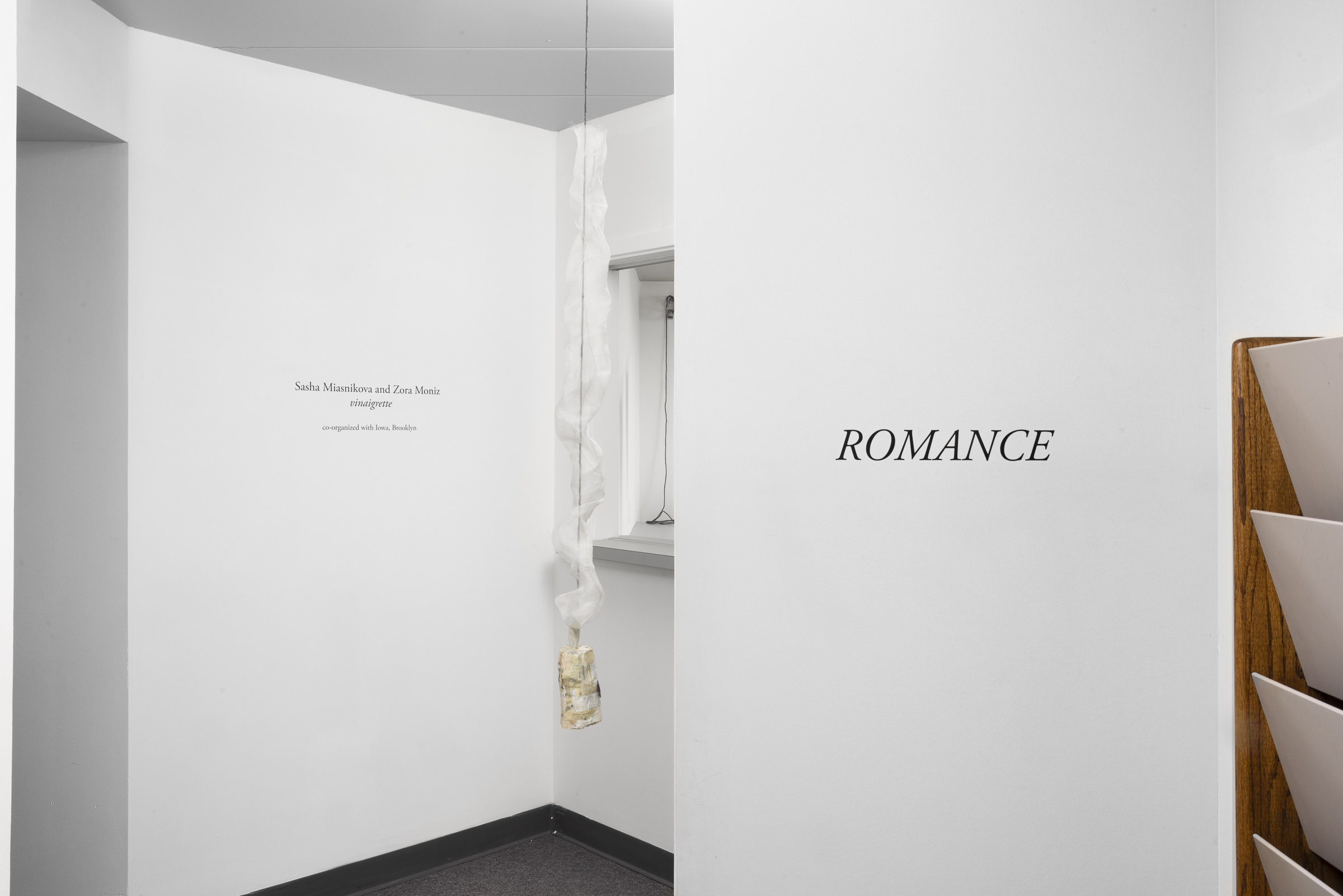

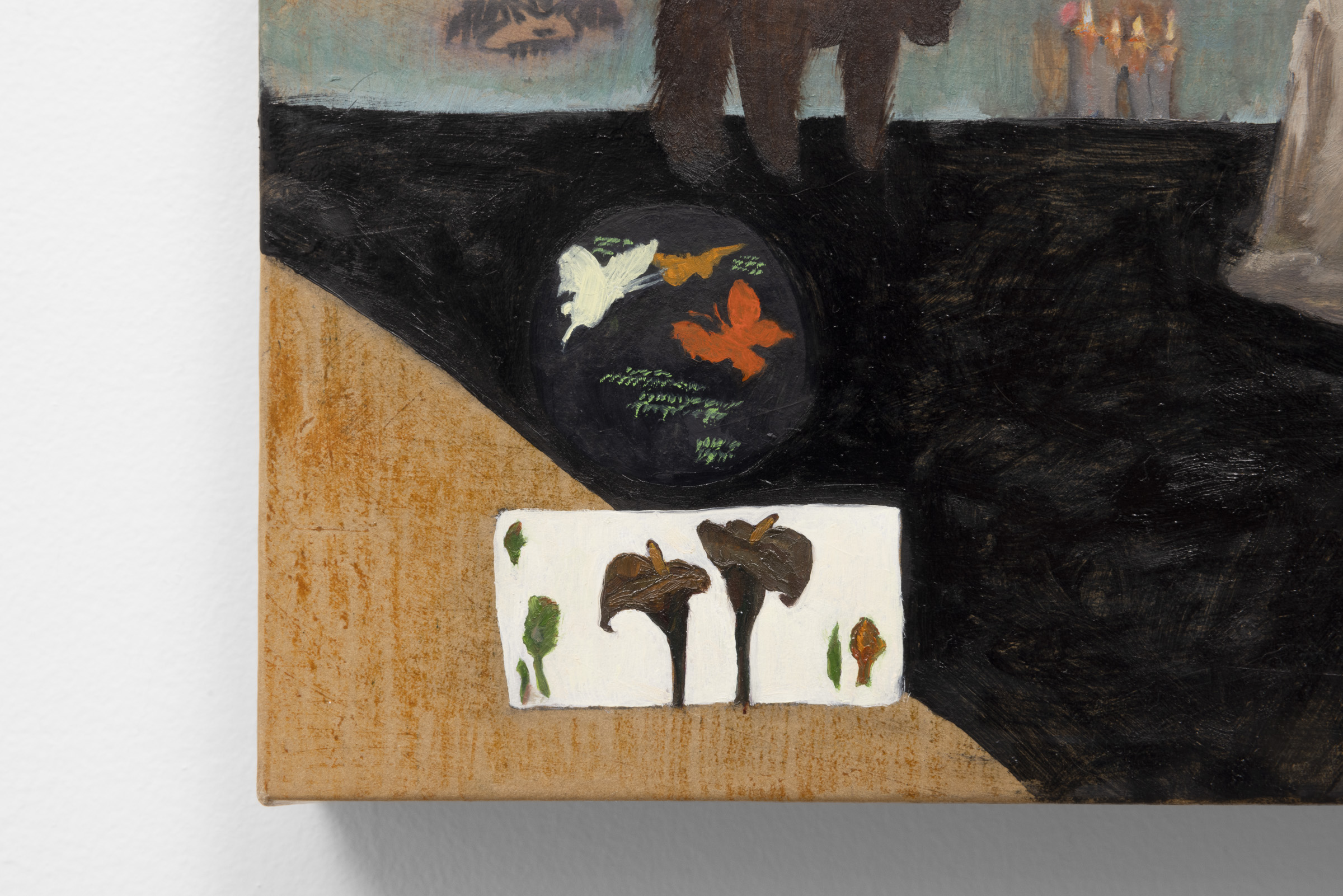

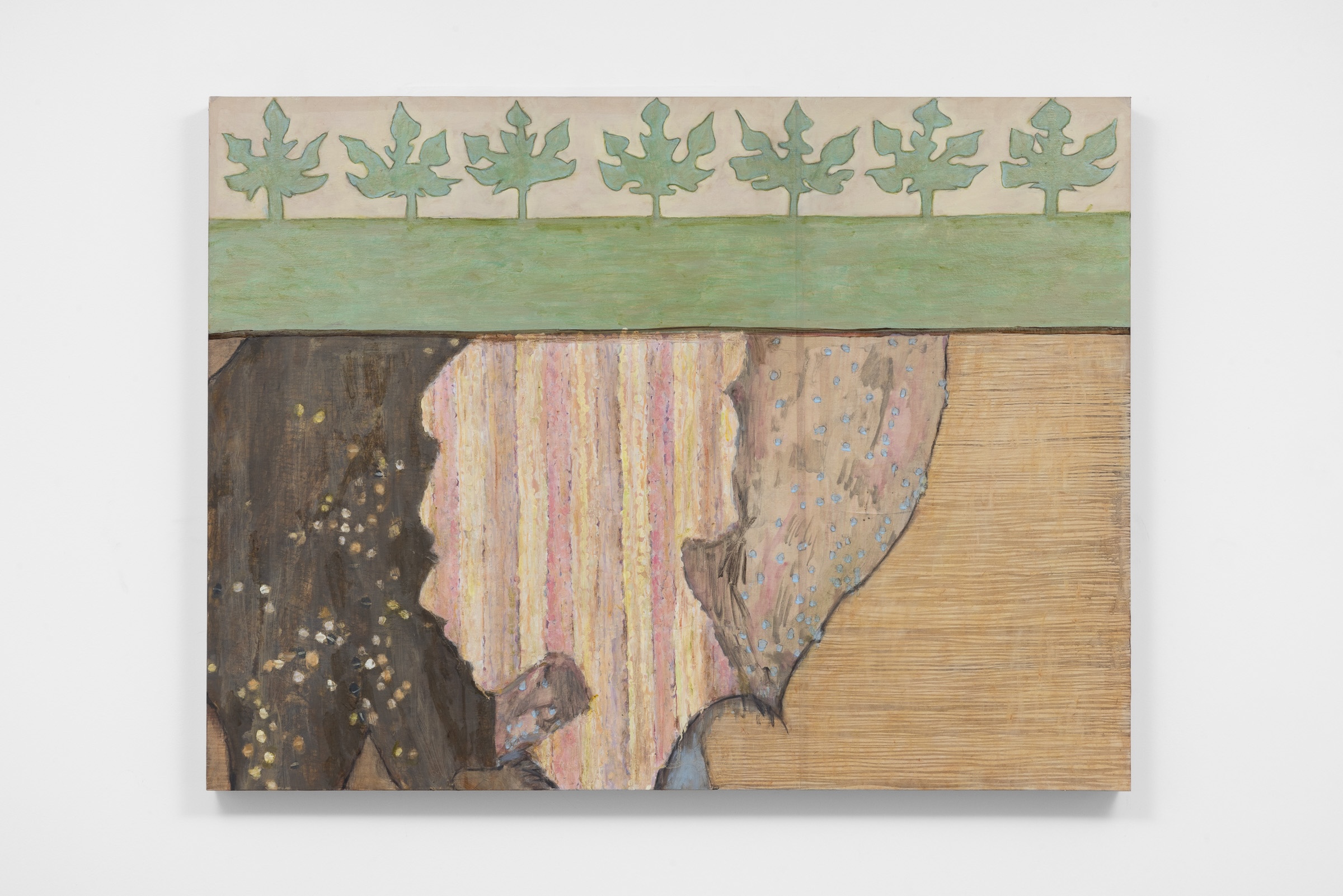

ROMANCE

Sasha Miasnikova and Zora Moniz

vinaigrette

Two-site exhibition with Iowa

Part I: Jan 17–March 1, 2026 (Brooklyn)

Part II: Jan 24–March 8, 2026 (Pittsburgh)